U.S. News

The Strong US Dollar Is Extending Pain in Emerging-Markets Currencies

Investors are betting the US dollar’s prolonged rise will hurt currencies ranging from the Hungarian forint to the Philippine peso, with the forint and the Polish zloty hitting fresh lows recently. The extended losses are another example of how the dollar’s strength is rippling through emerging-markets currencies and pressuring central banks across the globe to increase rates—even at the cost of a recession.

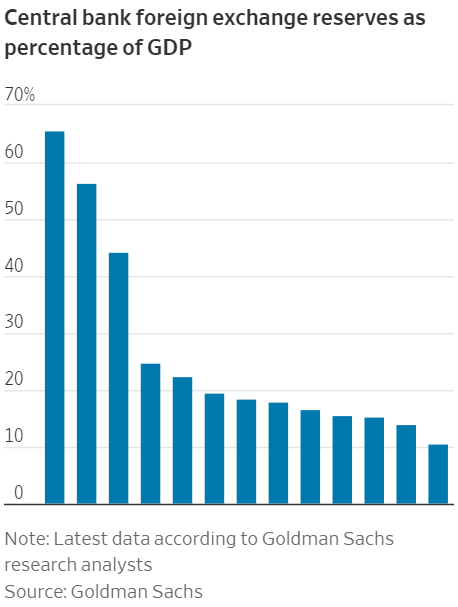

“Trouble is coming in emerging markets,” said Megan Greene, global economist and senior fellow at the Harvard Kennedy School, pointing toward Sri Lanka’s sovereign-debt crisis and drained foreign-exchange reserves. “It’s a familiar story in emerging markets and a sneak peek of what’s to come.”

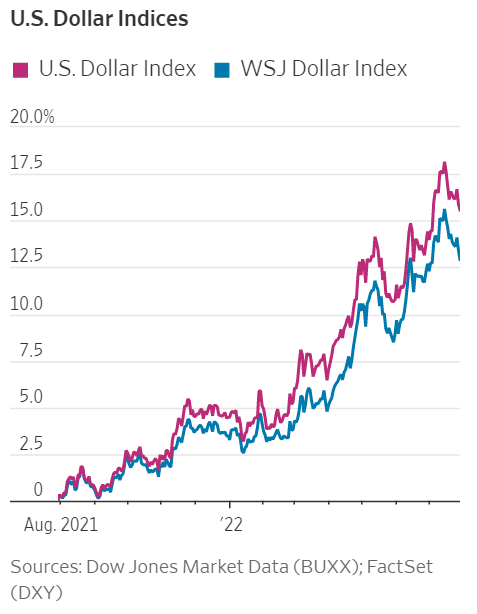

Wall Street firms that buy and sell currencies said clients have been increasingly focused on the ramifications of a stronger dollar. The WSJ Dollar Index, which measures the dollar against a basket of 16 currencies, is up around 13% over the past year. Worries about runaway inflation, fears of a global recession and a Federal Reserve moving aggressively to curb rising consumer prices have pushed the world’s reserve currency to multidecade highs. Its rise has outpaced analysts’ estimates, and many expect the greenback to run higher through year-end.

Get The New York Times and Financial Times Digital Subscription Combo 77% OFF

A strong dollar typically sends emerging-markets currencies into a tailspin. But this time around, emerging markets remained resilient throughout the first stage of the dollar’s rally, weathering external shocks such as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February and sharp moves in U.S. bond markets as the Fed reversed easy-money policies.

The narrative began to shift in June, when money managers started selling the South African rand and Brazilian real after buying them earlier in the year. The move lower coincided with softening commodity prices, removing the pillar that supports emerging-market economies backed by high-value exports such as copper and oil.

Get The Wall Street Journal Newspaper | WSJ Newspaper | WSJ Print Save 30% Off

Now, Goldman Sachs Group Inc. strategists said, “cracks are appearing” in emerging-market currencies after more than a year of beating returns against a basket of nine major currencies, including the Swiss franc and Canadian dollar.

“In recent days we continue to field questions about macroeconomic indications of emerging-market foreign exchange vulnerability,” said Kamakshya Trivedi, a Goldman analyst.

“In recent days we continue to field questions about macroeconomic indications of emerging-market foreign exchange vulnerability,” said Kamakshya Trivedi, a Goldman analyst.

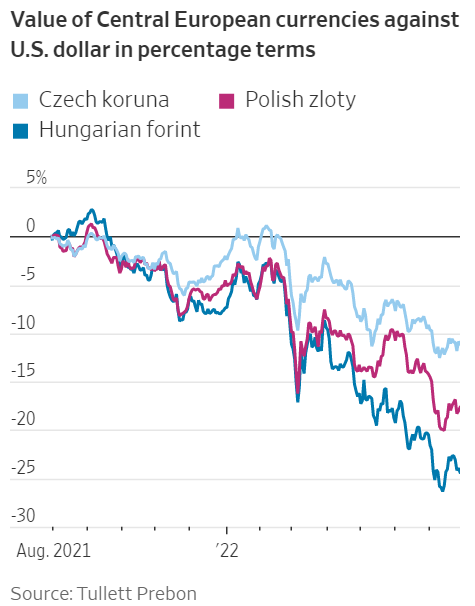

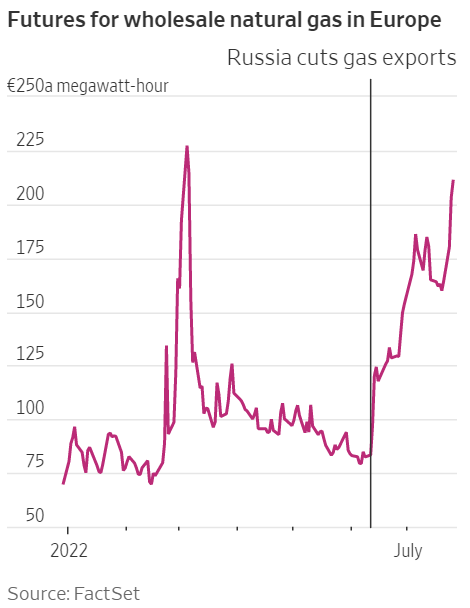

Hedge funds that bet on the direction of currencies are targeting Central European currencies next, labeling them as some of the most vulnerable because of the war in Ukraine. Portfolio managers are selling the forint and zloty as a wager on Europe’s potential energy crisis.

“If flows of gas are cut off this summer, those currencies will bear the brunt of it,” said Stephen Gallo, European head of foreign-exchange strategy for BMO Capital Markets.

The Hungarian forint and Polish zloty lost nearly 5% and 4% so far this month, respectively, against the US dollar. The Czech koruna is down over 2%. Analysts contend the koruna is the most resilient currency in Central Europe because the Czech National Bank built a stock of foreign-exchange reserves after the 2008 financial crisis.

A weaker currency can escalate inflation, exacerbating price increases for countries already grappling with rocketing energy and food prices. The problem is more acute for emerging-markets economies, which use the dollar to trade foreign goods and commodities.

Get The WSJ Print Edition – The Wall Street Journal Newspaper 52-Weeks Delivery Save 30% Off

Part of the dollar’s strength comes because currency investors have few alternatives. A gloomy investor outlook on important US trading partners, particularly Europe and Japan, is hurting currencies there. Political tumult in Italy and rising gas prices across Europe are thwarting gains in the euro, which recently dipped below parity against the US dollar for the first time since 2002.

How currencies fare can amount to a bet on whether investors think a country’s central bank will act aggressively to try to stop inflation.

Since the financial crisis, central banks worldwide slashed rates to near-zero to shore up markets and economies. Now they are moving at different paces to tighten borrowing conditions, breathing volatility into currency markets for the first time in decades.

Investors have pushed up the dollar in part because of the Fed’s tightening, which they think signals that the U.S. central bank will do what it takes to stop inflation. The value of the yen, meanwhile, has suffered because the Bank of Japan has kept easy-money policies in place.

Get Barron’s Digital Subscription 5 Years

Hungarian and Polish central banks have both raised rates in recent months, but with little effect on their respective currencies. Hungary’s central bank raised its key rate by 2 percentage points this month.

“Markets have a lot to digest,” said Seth Carpenter, chief global economist at Morgan Stanley. “Following the Covid shock, all major central banks were moving in the same direction, but no longer.”

The euro is down more than 10% year to date. Even though the European Central Bank raised rates for the first time since 2011 last week, the currency is failing to make significant gains because the ECB’s key interest rate is still at zero. The Fed on Wednesday raised its benchmark rate to a range between 2.25% and 2.5%.

The dollar lost some gains over the past week as investor expectations about the path of future interest-rate hikes diverged. Some money market managers are betting the Fed will reverse course and loosen borrowing conditions by the start of 2023. Lower rates would typically pull the dollar off its highs.