Economic News

The US Dollar Is Superstrong 8 Ways to Invest Abroad

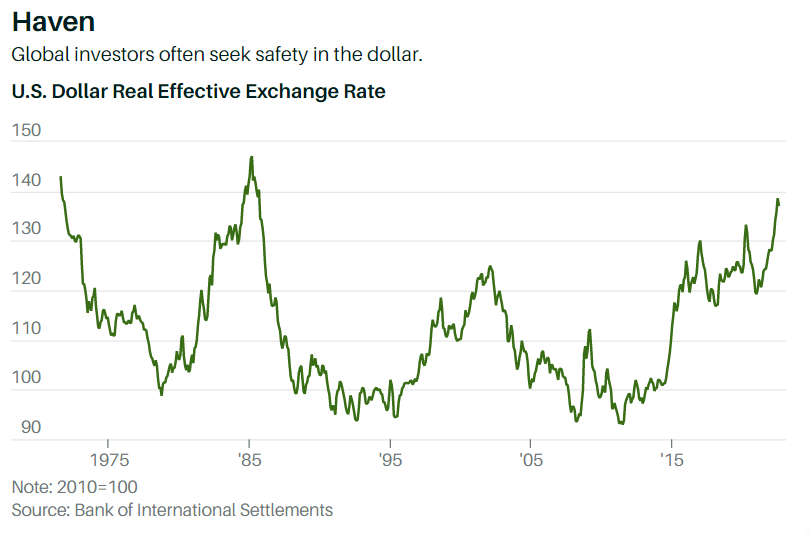

The U.S. dollar got a brief, welcome walloping this past week, falling 1.5% on Tuesday alone against a basket of six major currencies. It remains up a hefty 17% for the year, and close to its strongest level in decades. That matters for ordinary savers, and not just forex flippers.

In the weeks ahead, the dollar is likely to weigh on earnings for big U.S. multinationals. In the years ahead, it could hold back gains for S&P 500SPX –2.80% fund holders, judging by one recent analysis of the link between currency strength and returns. On the other hand, that means there is a double discount available now to U.S. shoppers in battered stock markets overseas. Japan looks particularly attractive.

Resist gut-renovating portfolios, however, to place a one-way bet on the buck. Its past could be priced in, its future is uncertain, and even its present is a matter of some dispute. One argument on Wall Street holds that the dollar isn’t as strong as it appears. Another says that we’re measuring its gains the wrong way.

Get The New York Times+Wall Street Journal 5-Year Digital Subscription, and take 77% off

Consider this a strong-dollar briefing for the macroeconomically exhausted—the investor who would rather study insurance accruals, rendered fat futures, or Kim Kardashian crypto tips than hear about one more abstract factor that has been whipsawing retirement stashes. We’ll avoid vulgar topics like swaps and bollinger bands; keep any mention of the Plaza Accord to a single sentence, not counting this one; and stick to established facts and convincing guesses of broad relevance to savers.

Financial motion is relative. If we say that Barry Bagholder has lost 56% this year on his AMC Entertainment Holdings AMC –8.29% (ticker: AMC) shares, we mean that he’s down that much compared with his U.S. dollars. But if unlucky Barry’s primary savings are in yen, his dollar-denominated shares have at least produced a favorable currency effect, cutting the loss from his meme-stock misadventure to 45%.

Currency gains and losses are quoted relative to other currencies. The U.S. dollar is up 15% this year against the euro; 20% on the British pound, or pound sterling; and 25% on the yen. The U.S. dollar index gives a sense of how the buck is doing more broadly. It’s dominated by the euro, yen, and British pound, with smaller weightings for the Canadian dollar, Swedish krona, and Swiss franc. This year, the index is up 17%. Late last month, you might have seen, it reached its highest level in 20 years.

Buy The Economist Digital Subscription 3-Years Save 70%

Already, we’ve stumbled into controversy. The dollar index was last rebalanced back when the euro was introduced. Its outdated currency weightings reflect historical importance, critics say, not how money is spent today.

The Federal Reserve tracks a broader index that rebalances each year for trade flows. It diminishes the euro, yen, and British pound in favor of China’s renminbi, sometimes called the yuan; Mexico’s peso; and a somewhat weightier Canadian dollar.

The U.S. dollar hasn’t done as well against those currencies this year—it’s down a smidgen against the Mexican peso. So the Fed’s trade-weighted dollar index is up only 11% on the year.

Bargain Hunting

Stocks in Europe and Japan look cheap based on price to earnings ratios.

| Country | Forward P/E |

|---|---|

| Italy | 7.1 |

| United Kingdom | 8.8 |

| Germany | 9.1 |

| Spain | 9.2 |

| Emerging Markets | 10.3 |

| France | 10.4 |

| Japan | 11.9 |

| World | 13.8 |

| Switzerland | 15.5 |

| U.S. | 15.9 |

This helps squash speculation about a new Plaza Accord—the 1985 agreement among monetary bigwigs at a posh New York hotel to weaken the U.S. dollar. It worked: Just ask parties to the Louvre Accord two years later, which sought to resuscitate the dollar.

Today’s strong dollar threatens growth by making U.S. exports more expensive, and it helps with inflation by making imports cheaper, the thinking goes. So, runaway dollar gains will persuade the Fed to pause the interest-rate hikes that have fueled the dollar’s rise. And since those hikes have also pummeled stocks and bonds this year, maybe we’re headed back to investor Valhalla, right?

Unlikely, and not just because the Fed’s trade-weighted view leaves the dollar less lofty. The threat to growth from a strong dollar is modest compared with the raging inflation that the Fed is fighting with interest-rate increases. Morgan Stanley’s economists estimate that a 10% rise in the trade-weighted dollar saps 0.4 percentage points from gross-domestic-product growth. “The broad-based tightening of financial conditions is very much a feature, not a bug, of the current policy stance,” they wrote this past week.

Get a 5-years subscription to the WSJ and Barrons News for $89

The strong dollar’s help in cooling inflation, meanwhile, is likely to be minimal for now. The U.S. invoices more than 95% of imports in dollars, the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City pointed out in a recent paper, so savings will unfold only gradually as producers adjust prices.

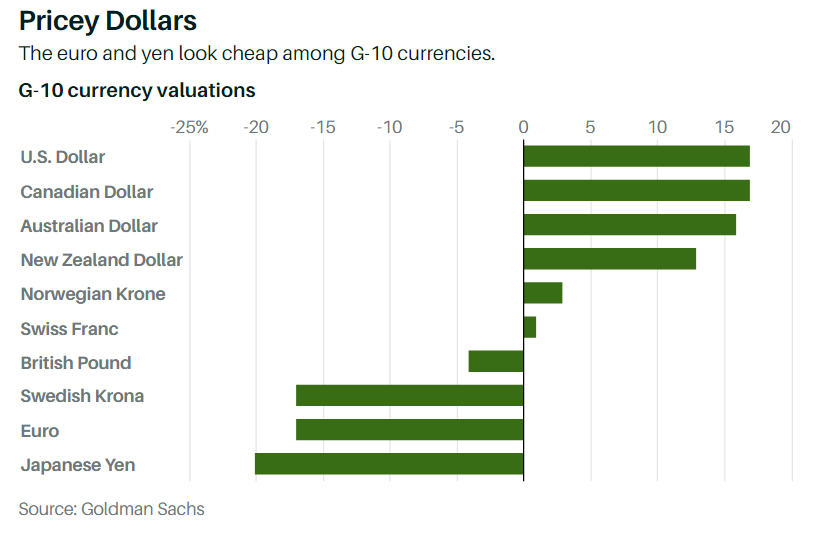

In fact, the strong dollar could weigh on U.S. stock returns for years, and boost returns for Americans who rebalance funds overseas, argues Ben Inker, co-head of asset allocation at money manager GMO. By his calculations, the buck is 17% overvalued, while the euro is undervalued by just as much, and the yen, by even more—20%.

An analysis of currency prices since 1970 shows that ones that were at least 16% too expensive went on to lose more than 5% over the following three years, while those that were at least 14% underpriced went on to gain nearly 9%.

Stock returns were similarly grouped, but more extreme. Shares in expensive-currency countries underperformed by 11 points over three years, while cheap-currency countries outperformed by nine points. Inker finds that this is explained by faster local earnings growth where currencies are cheap.

But that raises the question of how to tell which currencies are expensive or cheap, and not merely up or down a lot. One common method is called purchasing power parity. Divide the dollar cost of a bundle of goods and services in the U.S. by, say, the yen cost in Japan. If that ratio is much different than the exchange rate, there’s a mispricing. That theory makes sense, except to anyone who has visited another country.

Get The New York Times and Economist News Subscription 3-years for $89

“The problem with purchasing power parity is that currencies tend to spend a lot of the time—most of the time—trading very far away from it,” says Vassili Serebriakov, a currency and macro strategist at UBS. He refines the measure using other factors that influence currency demand. A key one lately for the U.S. is called terms of trade, and is equal to the ratio of export prices to import prices.

The U.S. has exported more energy than it has imported since 2019, while Europe and Japan remain big net importers. A spike in oil and gas prices, made worse by the war in Ukraine, has punished those economies, but has probably helped the U.S. economy more than it has hurt, says Serebriakov.

Buy Bloomberg Digital Subscription 5 Years for $60

The dollar is now about 12% overvalued, says Serebriakov, which is five points below its high point more than two decades ago. “We certainly think the dollar is expensive—make no mistake about that,” he says. “But the notion that it’s extreme or somehow misaligned with some of those fundamental drivers, we don’t buy into that.” This past week, Goldman Sachs predicted 5% to 7% more dollar upside.

We confess to having no special knowledge of exactly when the dollar will peak. Our in-house model uses a well-fed chicken and a bingo-board floor, and has lately produced more noise than signal. But a modest rebalancing in favor of non-U.S. markets feels deeply unpopular, borderline shameful, and thus perhaps wise, and may be even well-timed. And the currency discount is only part of it.

U.S. shares recently traded at 16 times forward earnings estimates, which is down 31% from last year’s high point, but close to their 20-year average, according to J.P. Morgan. Contrast that with euro-zone shares, which were down 45% from last year’s peak and 22% cheaper than the long-term average, and Japan’s shares, which were down 36% and cheaper by 18%, respectively. The U.S. dividend yield is 1.7%, versus 3.5% in the euro zone and 2.6% in Japan.

Get The Economist and The Wall Street Journal Bundle Digital Subscription for $89

Inker at GMO prefers Japan and emerging markets, and less so the euro zone, to the U.S., and calls an asset shift of 10 to 20 percentage points away from the U.S. a “pretty big move” for most investors. For context, U.S. shares were recently 61% of world stock market value, versus 15% for the euro zone and 5% for Japan.

Currency valuations vary widely across emerging markets, and some countries are more hurt than helped by a strong dollar, because payments on their dollar debt have risen in local currency. Europe faces the unique risk of its recent dependence on Russia for energy. Japan faces high energy costs, too, but “they’re going to be able to keep the heat on over the winter,” says Inker. He likes that many companies there have cash surpluses and the potential to improve returns on equity.

For individual stock buyers, J.P. Morgan recently recommended a mix of Japanese blue chips. Multinationals with price targets that suggest more than 30% upside include Suzuki Motor (7269.Japan), at 12 times earnings, and Hitachi (6501.Japan), at 10 times. Concordia Financial Group (7186.Japan), a bank at under 10 times earnings, has accelerating net interest income and a 4.2% dividend, and should benefit if interest rates rise. Seven & i Holdings (3382.Japan), a retailer, goes for 18 times earnings, or 14 times excluding goodwill charges. It’s seeing strong growth from overseas convenience stores, and could gain from Japan’s recent pandemic reopening at home.

Subscribe today and get 52 weeks of The WSJ Print Edition with daily delivery for $318

For fund buyers, there are low-fee index choices, like the iShares MSCI JapanEWJ –1.01% (EWJ) and Vanguard FTSE EuropeVGK –1.87% (VGK) exchange-traded funds. For emerging markets, there’s the SPDR Portfolio Emerging MarketsSPEM –2.02% (SPEM) ETF, but indexing there is awkward. Nearly half of the portfolio is in China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong, or as China likes to call them, China.

More broadly, many emerging markets are dominated by one or two giant firms, which helps explain Saudi Arabia’s 5% weighting. That’s an opportunity for small-cap stockpickers to earn their keep. Barron’s recently profiled Virtus KAR Emerging Markets Small-Cap fund (VAESX). Fees are high, at nearly 1.8% a year, but five-year performance ranks well, and China is held under 10%, topped by Brazil, South Korea, and India.

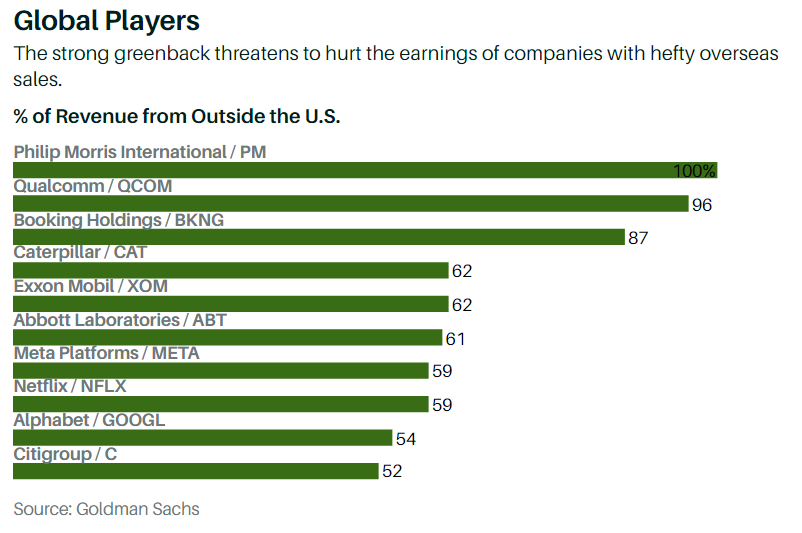

For U.S. holdings, don’t get too fancy by writing off U.S. exporters. Many are getting by just fine. Exxon Mobil (XOM), which does much of its business in dollars, cleared more cash in the second quarter than Alphabet (GOOGL).

Goldman calculates that U.S. companies with negligible overseas sales have already outperformed heavy exporters by 18 percentage points this year. Better to pick promising companies at good prices, and let management figure out how to handle currency swings.